オブジェクト指向プログラミング: DSA をマスターするための第一歩

Imagine you're walking through a bustling factory. You see different machines, each designed for a specific purpose, working together to create a final product. Some machines are similar but with slight modifications to perform specialized tasks. There's a clear organization: each machine encapsulates its own functionality, yet they inherit common traits from their predecessors, and they can be easily replaced or upgraded without disrupting the entire production line.

This factory is a perfect analogy for Object-Oriented Programming (OOP). In the world of code, our objects are like these machines – self-contained units with specific purposes, inheriting traits, and working together to build complex applications. Just as a factory manager organizes machines for efficient production, OOP helps developers organize code for efficient, maintainable, and scalable software development.

Course Outline

In this article, we'll explore the intricate world of OOP in JavaScript in our pursuit of mastering data structures and algorithms, covering:

- What is OOP and why it matters

-

Key concepts of OOP

- Encapsulation

- Inheritance

- Polymorphism

- Abstraction

- Objects and Classes in JavaScript

- Methods and Properties

- Constructor Functions and the new keyword

- this keyword and context in OOP

- Static methods and properties

- Private and public properties/methods (including symbols and weak maps)

- Getters and Setters

- Polymorphism and method overriding

- Object freezing, sealing, and preventing extensions

- Best practices for writing clean OOP code in JavaScript

- Small Project: Building a Library Management System

- Some Leetcode Problems on OOP

- Conclusion

- References

Let's dive in and start building our own code factory!

What is OOP and Why It Matters

Object-Oriented Programming is a programming paradigm that organizes code into objects, which are instances of classes. These objects contain data in the form of properties and code in the form of methods. OOP provides a structure for programs, making them more organized, flexible, and easier to maintain.

To illustrate OOP, let's consider a real-world example: A Car. In OOP terms, we can think of a car as an object with properties (like color, model, year) and methods (like start, accelerate, brake). Here's how we might represent this in JavaScript:

class Car {

constructor(color, model, year) {

this.color = color;

this.model = model;

this.year = year;

}

start() {

console.log(`The ${this.color} ${this.model} is starting.`);

}

accelerate() {

console.log(`The ${this.color} ${this.model} is accelerating.`);

}

brake() {

console.log(`The ${this.color} ${this.model} is braking.`);

}

}

const myCar = new Car("red", "Toyota", 2020);

myCar.start(); // The red Toyota is starting.

myCar.accelerate(); // The red Toyota is accelerating.

myCar.brake(); // The red Toyota is braking.

Why does OOP matter?

- Organization: OOP helps in organizing complex code into manageable, reusable structures.

- Modularity: Objects can be separated and maintained independently, making debugging and updating easier.

- Reusability: Once an object is created, it can be reused in different parts of the program or even in different programs.

- Scalability: OOP makes it easier to build and maintain larger applications.

- Real-world modeling: OOP concepts often align well with real-world objects and scenarios (just like our car example), making it intuitive to model complex systems.

Key Concepts of OOP

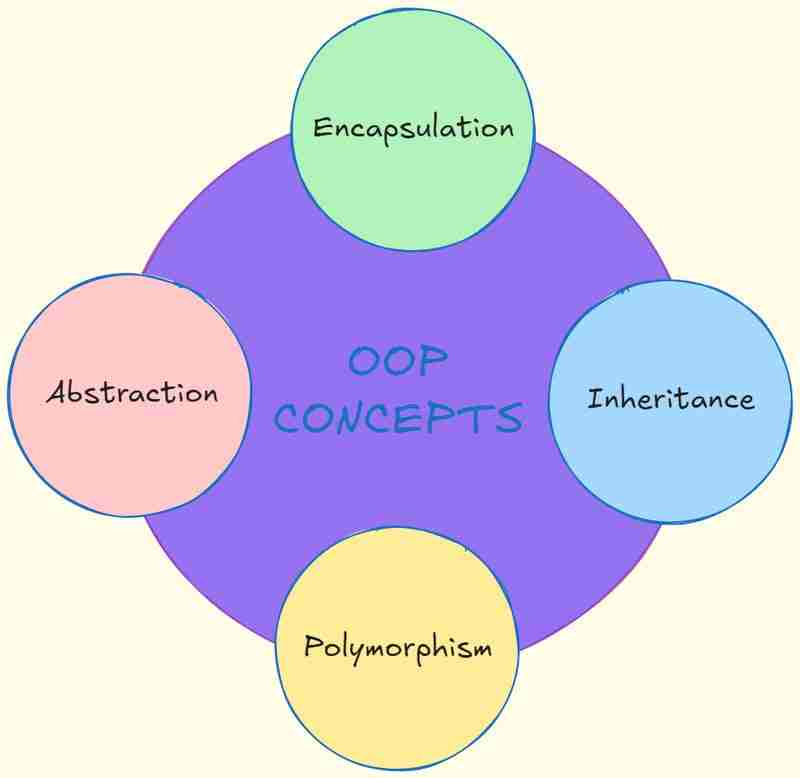

In OOP, there are four key concepts that we cannot ignore, they are:

1. Encapsulation

Encapsulation is the bundling of data and the methods that operate on that data within a single unit (object). It restricts direct access to some of an object's components, which is a means of preventing accidental interference and misuse of the methods and data.

class BankAccount {

#balance = 0; // Private field; it can only be accessed within the class

// private balance = 0; // this is the same as #balance

deposit(amount) {

if (amount > 0) {

this.#balance = amount;

console.log(`Deposited ${amount}. New balance: ${this.#balance}`);

}

}

getBalance() {

return this.#balance;

}

}

const account = new BankAccount();

account.deposit(100);

console.log(account.getBalance()); // 100

// console.log(account.#balance); // This would throw an error

In this example, #balance is a private field, encapsulated within the BankAccount class. It can only be accessed and modified through the class methods, ensuring data integrity.

2. Inheritance

Inheritance allows a class to inherit properties and methods from another class. This promotes code reuse and establishes a relationship between parent and child classes.

class Animal {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

speak() {

console.log(`${this.name} makes a sound.`);

}

}

class Dog extends Animal {

speak() {

console.log(`${this.name} barks.`);

}

}

const dog = new Dog("Buddy");

dog.speak(); // Outputs: Buddy barks.

Here, Dog inherits from Animal (since Animal is the parent class, meaning all Dog objects are also Animal objects with their own name property), reusing the name property and overriding the speak method.

3. Polymorphism

Polymorphism allows objects of different classes to be treated as objects of a common parent class. It enables the same interface to be used for different underlying forms (data types).

class Shape {

area() {

return 0;

}

}

class Circle extends Shape {

constructor(radius) {

super();

this.radius = radius;

}

area() {

return Math.PI * this.radius ** 2;

}

}

class Rectangle extends Shape {

constructor(width, height) {

super();

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

area() {

return this.width * this.height;

}

}

function printArea(shape) {

console.log(`Area: ${shape.area()}`);

}

const circle = new Circle(5);

const rectangle = new Rectangle(4, 5);

printArea(circle); // Area: 78.53981633974483

printArea(rectangle); // Area: 20

In this example, printArea function can work with any shape that has an area method, demonstrating polymorphism. Since Circle and Rectangle are both shapes, they are expected to have an area method, though they may have different implementations.

4. Abstraction

Abstraction is the process of hiding complex implementation details and showing only the necessary features of an object. It helps in reducing programming complexity and effort.

class Vehicle {

constructor(make, model) {

this.make = make;

this.model = model;

}

start() {

return "Vehicle started";

}

stop() {

return "Vehicle stopped";

}

}

class Car extends Vehicle {

start() {

return `${this.make} ${this.model} engine started`;

}

}

const myCar = new Car("Toyota", "Corolla");

console.log(myCar.start()); // Toyota Corolla engine started

console.log(myCar.stop()); // Vehicle stopped

Here, Vehicle provides an abstraction for different types of vehicles. The Car class uses this abstraction and provides its own implementation where needed.

Objects and Classes in JavaScript

In JavaScript, objects are standalone entities with properties and methods. Classes, introduced in ES6, provide a cleaner, more compact alternative to constructor functions and prototypes. Let's explore both approaches:

Objects

Objects can be created using object literals:

const person = {

name: "John",

age: 30,

greet() {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.name}`);

},

};

console.log(person.name); // John

person.greet(); // Hello, my name is John

Classes

Classes are templates for creating objects. This means that they define the structure and behavior that all instances of the class will have. In other words, classes serve as blueprints for creating multiple objects with similar properties and methods. When you create an object from a class (using the new keyword), you're creating an instance of that class, which inherits all the properties and methods defined in the class.

Note: It is important to note that when you instantiate a class, the constructor method is called automatically. This method is used to initialize the object's properties. Also, it is just an instance that is been created when you use the new keyword.

class Person {

constructor(name, age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

greet() {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.name}`);

}

}

const john = new Person("John", 30);

john.greet(); // Hello, my name is John

Methods and Properties

Methods are functions that belong to an object, while properties are the object's data.

class Car {

constructor(make, model) {

this.make = make; // Property

this.model = model; // Property

this.speed = 0; // Property

}

// Method

accelerate(amount) {

this.speed = amount;

console.log(`${this.make} ${this.model} is now going ${this.speed} mph`);

}

// Method

brake(amount) {

this.speed = Math.max(0, this.speed - amount);

console.log(`${this.make} ${this.model} slowed down to ${this.speed} mph`);

}

}

const myCar = new Car("Tesla", "Model 3");

myCar.accelerate(50); // Tesla Model 3 is now going 50 mph

myCar.brake(20); // Tesla Model 3 slowed down to 30 mph

Constructor Functions and the new Keyword

Before ES6 classes, constructor functions were used to create objects:

function Person(name, age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.greet = function () {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.name}`);

};

}

const john = new Person("John", 30);

john.greet(); // Hello, my name is John

The new keyword:

- Creates a new empty object

- Sets this to point to that object (the newly created object can now be accessed using the this keyword)

- Calls the constructor function to initialize the object

- Returns the object (implicitly)

this Keyword and Context in OOP

In JavaScript, this refers to the object that is executing the current function. Its value can change depending on how a function is called. Let's take a look at some examples:

1. Global Context

When used in the global context (outside any function or object), this refers to the global object (window in browsers or global in Node.js).

console.log(this); // In browsers, this will log the 'window' object

2. Inside an Object Method

When this is used inside a method of an object, it refers to the object that owns the method.

const person = {

name: "Alice",

sayHello: function () {

console.log(this.name); // 'this' refers to the 'person' object

},

};

person.sayHello(); // Output: Alice

3. Inside a Regular Function

In a regular function, this refers to the global object (window in browsers or global in Node.js), unless in strict mode (use strict), where this is undefined.

function showThis() {

console.log(this); // 'this' refers to the global object in non-strict mode

}

showThis(); // In browsers, it logs the 'window' object

4. Inside a Constructor Function

When using a constructor function, this refers to the newly created object.

function Car(brand) {

this.brand = brand;

}

const myCar = new Car("Toyota");

console.log(myCar.brand); // Output: Toyota

5. Inside a Class

When used in a class method, this refers to the instance of the class.

class Animal {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

speak() {

console.log(`${this.name} makes a sound.`);

}

}

const dog = new Animal("Dog");

dog.speak(); // Output: Dog makes a sound.

6. Using this in an Event Handler

In event handlers, this refers to the HTML element that received the event

7. Arrow Functions and Lexical this

In arrow functions, this is lexically scoped, meaning it inherits this from the surrounding context.

const person = {

name: "Bob",

greet: function () {

const arrowFunc = () => {

console.log(this.name); // 'this' refers to the 'person' object

};

arrowFunc();

},

};

person.greet(); // Output: Bob

- call, apply, and bind Methods You can explicitly set the value of this using call, apply, or bind.

// call

function greet() {

console.log(`Hello, ${this.name}`);

}

const user = { name: "John" };

greet.call(user); // Output: Hello, John

// apply (similar to call but with arguments as an array):

function introduce(greeting, age) {

console.log(`${greeting}, I'm ${this.name} and I'm ${age} years old.`);

}

const user = { name: "Emily" };

introduce.apply(user, ["Hi", 25]); // Output: Hi, I'm Emily and I'm 25 years old.

// bind (returns a new function with this bound):

function sayName() {

console.log(this.name);

}

const user = { name: "Lucy" };

const boundFunc = sayName.bind(user);

boundFunc(); // Output: Lucy

Static Methods and Properties

Static methods and properties belong to the class itself rather than to instances of the class. Remember, we said earlier that whenever you instantiate a class, it is an instance of the class that is created, not the class itself. Based on this, we can say that static methods and properties are used to create methods and properties that are related to the class but not to any particular instance of the class.

class MathOperations {

static PI = 3.14159;

static square(x) {

return x * x;

}

static cube(x) {

return x * x * x;

}

}

// Accessing static properties and methods directly from the class

console.log(MathOperations.PI); // 3.14159

console.log(MathOperations.square(4)); // 16

console.log(MathOperations.cube(3)); // 27

// Accessing static properties and methods through an instance (This will not work)

const mathOperations = new MathOperations();

console.log(mathOperations.PI); // undefined

console.log(mathOperations.square(4)); // TypeError: mathOperations.square is not a function

console.log(mathOperations.cube(3)); // TypeError: mathOperations.cube is not a function

Private and Public Properties/Methods

JavaScript has several ways to implement private properties and methods:

Using Symbols

const _radius = Symbol("radius");

class Circle {

constructor(radius) {

this[_radius] = radius;

}

get area() {

return Math.PI * this[_radius] ** 2;

}

}

const circle = new Circle(5);

console.log(circle.area); // 78.53981633974483

console.log(circle[_radius]); // undefined (the property is private - can not be accessed outside the class)

Using WeakMaps

const _radius = new WeakMap();

class Circle {

constructor(radius) {

_radius.set(this, radius);

}

get area() {

return Math.PI * _radius.get(this) ** 2;

}

}

const circle = new Circle(5);

console.log(circle.area); // 78.53981633974483

console.log(_radius.get(circle)); // 5

Using Private Fields (ES2022)

class Circle {

#radius;

constructor(radius) {

this.#radius = radius;

}

get area() {

return Math.PI * this.#radius ** 2;

}

}

const circle = new Circle(5);

console.log(circle.area); // 78.53981633974483

// console.log(circle.#radius); // SyntaxError

Getters and Setters

Getters and setters allow you to define object accessors (computed properties):

class Temperature {

constructor(celsius) {

this._celsius = celsius;

}

get fahrenheit() {

return (this._celsius * 9) / 5 32;

}

set fahrenheit(value) {

this._celsius = ((value - 32) * 5) / 9;

}

get celsius() {

return this._celsius;

}

set celsius(value) {

if (value

Polymorphism and Method Overriding

Polymorphism allows objects of different types to be treated as objects of a common parent class. Method overriding is a form of polymorphism where a subclass provides a specific implementation of a method that is already defined in its parent class.

class Shape {

area() {

return 0;

}

toString() {

return `Area: ${this.area()}`;

}

}

class Circle extends Shape {

constructor(radius) {

super();

this.radius = radius;

}

area() {

return Math.PI * this.radius ** 2;

}

}

class Rectangle extends Shape {

constructor(width, height) {

super();

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

area() {

return this.width * this.height;

}

}

const shapes = [new Circle(5), new Rectangle(4, 5)];

shapes.forEach((shape) => {

console.log(shape.toString());

});

// Output:

// Area: 78.53981633974483

// Area: 20

Notice how both the Circle and Rectangle classes have a toString method (which we inherited from the Shape class - the parent class). However, the toString method in the Circle class overrides the toString method in the Shape class. This is an example of polymorphism and method overriding.

Object Freezing, Sealing, and Preventing Extensions

// Object.freeze() - Prevents adding, removing, or modifying properties

const frozenObj = Object.freeze({

prop: 42,

});

frozenObj.prop = 33; // Fails silently in non-strict mode

console.log(frozenObj.prop); // 42

// Object.seal() - Prevents adding new properties and marking existing properties as non-configurable

const sealedObj = Object.seal({

prop: 42,

});

sealedObj.prop = 33; // This works

sealedObj.newProp = "new"; // This fails silently in non-strict mode

console.log(sealedObj.prop); // 33

console.log(sealedObj.newProp); // undefined

// Object.preventExtensions() - Prevents adding new properties

const nonExtensibleObj = Object.preventExtensions({

prop: 42,

});

nonExtensibleObj.prop = 33; // This works

nonExtensibleObj.newProp = "new"; // This fails silently in non-strict mode

console.log(nonExtensibleObj.prop); // 33

console.log(nonExtensibleObj.newProp); // undefined

These methods are useful for creating immutable objects or preventing accidental modifications to objects.

Best Practices for Writing Clean OOP Code in JavaScript

Use ES6 Classes: They provide a cleaner, more intuitive syntax for creating objects and implementing inheritance.

Follow the Single Responsibility Principle: Each class should have a single, well-defined purpose.

// Good ✅

class User {

constructor(name, email) {

this.name = name;

this.email = email;

}

}

class UserValidator {

static validateEmail(email) {

// Email validation logic

}

}

// Not so good ❌

class User {

constructor(name, email) {

this.name = name;

this.email = email;

}

validateEmail() {

// Email validation logic

}

}

-

Use Composition Over Inheritance: Favor object composition over class inheritance when designing larger systems.

// Composition

class Engine {

start() {

/* ... */

}

}

class Car {

constructor() {

this.engine = new Engine();

}

start() {

this.engine.start();

}

}

// Inheritance

class Vehicle {

start() {

/* ... */

}

}

class Car extends Vehicle {

// ...

}

Implement Private Fields: Use the latest JavaScript features or closures to create truly private fields.

Use Getters and Setters: They provide more control over how properties are accessed and modified.

Avoid Overusing this: Use object destructuring in methods to make the code cleaner and less prone to errors.

class Rectangle {

constructor(width, height) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

area() {

const { width, height } = this;

return width * height;

}

}

-

Use Method Chaining: It can make your code more readable and concise.

class Calculator {

constructor() {

this.value = 0;

}

add(n) {

this.value = n;

return this;

}

subtract(n) {

this.value -= n;

return this;

}

result() {

return this.value;

}

}

const calc = new Calculator();

console.log(calc.add(5).subtract(2).result()); // 3

Favor Declarative Over Imperative Programming: Use higher-order functions like map, filter, and reduce when working with collections.

Use Static Methods Appropriately: Use static methods for utility functions that don't require access to instance-specific data.

Write Self-Documenting Code: Use clear, descriptive names for classes, methods, and properties. Add comments only when necessary to explain complex logic.

Small Project: Building a Library Management System

Let's put our OOP knowledge into practice by building a simple Library Management System.

class Book {

constructor(title, author, isbn) {

this.title = title;

this.author = author;

this.isbn = isbn;

this.isAvailable = true;

}

checkout() {

if (this.isAvailable) {

this.isAvailable = false;

return true;

}

return false;

}

return() {

this.isAvailable = true;

}

}

class Library {

constructor() {

this.books = [];

}

addBook(book) {

this.books.push(book);

}

findBookByISBN(isbn) {

return this.books.find((book) => book.isbn === isbn);

}

checkoutBook(isbn) {

const book = this.findBookByISBN(isbn);

if (book) {

return book.checkout();

}

return false;

}

returnBook(isbn) {

const book = this.findBookByISBN(isbn);

if (book) {

book.return();

return true;

}

return false;

}

get availableBooks() {

return this.books.filter((book) => book.isAvailable);

}

}

// Usage

const library = new Library();

library.addBook(

new Book("The Great Gatsby", "F. Scott Fitzgerald", "9780743273565")

);

library.addBook(

new Book("To Kill a Mockingbird", "Harper Lee", "9780446310789")

);

console.log(library.availableBooks.length); // 2

library.checkoutBook("9780743273565");

console.log(library.availableBooks.length); // 1

library.returnBook("9780743273565");

console.log(library.availableBooks.length); // 2

This project demonstrates the use of classes, encapsulation, methods, and properties in a real-world scenario.

Some Leetcode Problems on OOP

To further practice your OOP skills in JavaScript, try solving these problems:

- LeetCode: Design Parking System

- LeetCode: Design HashMap

- Codewars: Object Oriented Piracy

Conclusion

Object-Oriented Programming is a powerful paradigm that helps organize and structure code in a way that mirrors real-world objects and relationships. In this article, we've covered the fundamental concepts of OOP in JavaScript, from basic object creation to advanced topics like polymorphism and best practices.

Key takeaways:

- OOP helps in creating modular, reusable, and maintainable code.

- JavaScript provides multiple ways to implement OOP concepts, with ES6 classes offering a clean and intuitive syntax.

- Principles like encapsulation, inheritance, polymorphism, and abstraction form the backbone of OOP.

- Best practices, such as using composition over inheritance and following the single responsibility principle, can greatly improve code quality.

As you continue your journey with OOP in JavaScript, remember that practice is key. Try to apply these concepts in your projects, refactor existing code to follow OOP principles, and don't be afraid to explore advanced patterns and techniques.

References

For further reading and practice, check out these resources:

- MDN Web Docs: Object-oriented JavaScript

- JavaScript.info: Classes

- You Don't Know JS: this & Object Prototypes

- Eloquent JavaScript: Chapter 6: The Secret Life of Objects

Remember, mastering OOP is a journey. Keep coding, keep learning, and most importantly, enjoy the process of creating robust and elegant object-oriented JavaScript applications!

Stay Updated and Connected

To ensure you don't miss any part of this series and to connect with me for more in-depth discussions on Software Development (Web, Server, Mobile or Scraping / Automation), OOP, data structures and algorithms, and other exciting tech topics, follow me on:

- GitHub

- X (Twitter)

Stay tuned and happy coding ???

-

macOS 上の Django で「ImproperlyConfigured: MySQLdb モジュールのロード中にエラーが発生しました」を修正する方法?MySQL の不適切な構成: 相対パスの問題Django で python manage.py runserver を実行すると、次のエラーが発生する場合があります:ImproperlyConfigured: Error loading MySQLdb module: dlopen(/Library...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開

macOS 上の Django で「ImproperlyConfigured: MySQLdb モジュールのロード中にエラーが発生しました」を修正する方法?MySQL の不適切な構成: 相対パスの問題Django で python manage.py runserver を実行すると、次のエラーが発生する場合があります:ImproperlyConfigured: Error loading MySQLdb module: dlopen(/Library...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開 -

Go で WebSocket を使用してリアルタイム通信を行うチャット アプリケーション、ライブ通知、共同作業ツールなど、リアルタイムの更新が必要なアプリを構築するには、従来の HTTP よりも高速でインタラクティブな通信方法が必要です。そこで WebSocket が登場します。今日は、アプリケーションにリアルタイム機能を追加できるように、Go で WebSo...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開

Go で WebSocket を使用してリアルタイム通信を行うチャット アプリケーション、ライブ通知、共同作業ツールなど、リアルタイムの更新が必要なアプリを構築するには、従来の HTTP よりも高速でインタラクティブな通信方法が必要です。そこで WebSocket が登場します。今日は、アプリケーションにリアルタイム機能を追加できるように、Go で WebSo...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開 -

MySQL を使用して今日が誕生日のユーザーを見つけるにはどうすればよいですか?MySQL を使用して今日の誕生日を持つユーザーを識別する方法MySQL を使用して今日がユーザーの誕生日かどうかを判断するには、誕生日が一致するすべての行を検索する必要があります。今日の日付。これは、UNIX タイムスタンプとして保存された誕生日と今日の日付を比較する単純な MySQL クエリを通...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開

MySQL を使用して今日が誕生日のユーザーを見つけるにはどうすればよいですか?MySQL を使用して今日の誕生日を持つユーザーを識別する方法MySQL を使用して今日がユーザーの誕生日かどうかを判断するには、誕生日が一致するすべての行を検索する必要があります。今日の日付。これは、UNIX タイムスタンプとして保存された誕生日と今日の日付を比較する単純な MySQL クエリを通...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開 -

「if」ステートメントを超えて: 明示的な「bool」変換を伴う型をキャストせずに使用できる場所は他にありますか?キャストなしで bool へのコンテキスト変換が可能クラスは bool への明示的な変換を定義し、そのインスタンス 't' を条件文で直接使用できるようにします。ただし、この明示的な変換では、キャストなしで bool として 't' を使用できる場所はどこですか?コン...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開

「if」ステートメントを超えて: 明示的な「bool」変換を伴う型をキャストせずに使用できる場所は他にありますか?キャストなしで bool へのコンテキスト変換が可能クラスは bool への明示的な変換を定義し、そのインスタンス 't' を条件文で直接使用できるようにします。ただし、この明示的な変換では、キャストなしで bool として 't' を使用できる場所はどこですか?コン...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開 -

Bootstrap 4 ベータ版の列オフセットはどうなりましたか?Bootstrap 4 ベータ: 列オフセットの削除と復元Bootstrap 4 は、ベータ 1 リリースで、その方法に大幅な変更を導入しました。列がオフセットされました。ただし、その後の Beta 2 リリースでは、これらの変更は元に戻されました。offset-md-* から ml-autoBoo...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開

Bootstrap 4 ベータ版の列オフセットはどうなりましたか?Bootstrap 4 ベータ: 列オフセットの削除と復元Bootstrap 4 は、ベータ 1 リリースで、その方法に大幅な変更を導入しました。列がオフセットされました。ただし、その後の Beta 2 リリースでは、これらの変更は元に戻されました。offset-md-* から ml-autoBoo...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開 -

データ挿入時の「一般エラー: 2006 MySQL サーバーが消えました」を修正するにはどうすればよいですか?レコードの挿入中に「一般エラー: 2006 MySQL サーバーが消えました」を解決する方法はじめに:MySQL データベースにデータを挿入すると、「一般エラー: 2006 MySQL サーバーが消えました。」というエラーが発生することがあります。このエラーは、通常、MySQL 構成内の 2 つの変...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開

データ挿入時の「一般エラー: 2006 MySQL サーバーが消えました」を修正するにはどうすればよいですか?レコードの挿入中に「一般エラー: 2006 MySQL サーバーが消えました」を解決する方法はじめに:MySQL データベースにデータを挿入すると、「一般エラー: 2006 MySQL サーバーが消えました。」というエラーが発生することがあります。このエラーは、通常、MySQL 構成内の 2 つの変...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開 -

一意の ID を保持し、重複した名前を処理しながら、PHP で 2 つの連想配列を結合するにはどうすればよいですか?PHP での連想配列の結合PHP では、2 つの連想配列を 1 つの配列に結合するのが一般的なタスクです。次のリクエストを考えてみましょう:問題の説明:提供されたコードは 2 つの連想配列 $array1 と $array2 を定義します。目標は、両方の配列のすべてのキーと値のペアを統合する新しい配...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開

一意の ID を保持し、重複した名前を処理しながら、PHP で 2 つの連想配列を結合するにはどうすればよいですか?PHP での連想配列の結合PHP では、2 つの連想配列を 1 つの配列に結合するのが一般的なタスクです。次のリクエストを考えてみましょう:問題の説明:提供されたコードは 2 つの連想配列 $array1 と $array2 を定義します。目標は、両方の配列のすべてのキーと値のペアを統合する新しい配...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開 -

情報の損失を避けるために、異なるレコードを持つデータを正確にピボットするにはどうすればよいですか?個別のレコードを効果的にピボットするピボット クエリは、データを表形式に変換し、簡単なデータ分析を可能にする上で重要な役割を果たします。ただし、個別のレコードを扱う場合、ピボット クエリのデフォルトの動作に問題が生じる可能性があります。問題: 個別の値の無視次の表を検討してください:--------...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開

情報の損失を避けるために、異なるレコードを持つデータを正確にピボットするにはどうすればよいですか?個別のレコードを効果的にピボットするピボット クエリは、データを表形式に変換し、簡単なデータ分析を可能にする上で重要な役割を果たします。ただし、個別のレコードを扱う場合、ピボット クエリのデフォルトの動作に問題が生じる可能性があります。問題: 個別の値の無視次の表を検討してください:--------...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 27 日に公開 -

C と C++ が関数シグネチャの配列の長さを無視するのはなぜですか?C および C の関数に配列を渡す 質問:なぜ C と C では、 C コンパイラでは、int dis(char a[1]) などの関数シグネチャでの配列長宣言が許可されていない場合でも許可されます。 enforced?答え:C および C で配列を関数に渡すために使用される構文は、最初の要素へのポ...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開

C と C++ が関数シグネチャの配列の長さを無視するのはなぜですか?C および C の関数に配列を渡す 質問:なぜ C と C では、 C コンパイラでは、int dis(char a[1]) などの関数シグネチャでの配列長宣言が許可されていない場合でも許可されます。 enforced?答え:C および C で配列を関数に渡すために使用される構文は、最初の要素へのポ...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開 -

MySQL でアクセントを削除してオートコンプリート検索を改善するにはどうすればよいですか?効率的なオートコンプリート検索のために MySQL でアクセントを削除する地名の大規模なデータベースを管理する場合、正確かつ効率的であることを保証することが重要ですデータの取得。地名にアクセントがあると、オートコンプリート機能を使用するときに問題が発生する可能性があります。これに対処するには、当然の...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開

MySQL でアクセントを削除してオートコンプリート検索を改善するにはどうすればよいですか?効率的なオートコンプリート検索のために MySQL でアクセントを削除する地名の大規模なデータベースを管理する場合、正確かつ効率的であることを保証することが重要ですデータの取得。地名にアクセントがあると、オートコンプリート機能を使用するときに問題が発生する可能性があります。これに対処するには、当然の...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開 -

MySQL で複合外部キーを実装するにはどうすればよいですか?SQL での複合外部キーの実装一般的なデータベース設計の 1 つは、複合キーを使用してテーブル間の関係を確立することです。複合キーは、テーブル内のレコードを一意に識別する複数の列の組み合わせです。このシナリオでは、チュートリアルとグループの 2 つのテーブルがあり、チュートリアルの複合一意キーをグル...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開

MySQL で複合外部キーを実装するにはどうすればよいですか?SQL での複合外部キーの実装一般的なデータベース設計の 1 つは、複合キーを使用してテーブル間の関係を確立することです。複合キーは、テーブル内のレコードを一意に識別する複数の列の組み合わせです。このシナリオでは、チュートリアルとグループの 2 つのテーブルがあり、チュートリアルの複合一意キーをグル...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開 -

Java で JComponent が背景画像の後ろに隠れるのはなぜですか?背景画像で隠された JComponent のデバッグJava アプリケーションで JLabel などの JComponent を操作する場合、適切な動作を保証することが重要です。そして視認性。コンポーネントが背景画像の背後に隠れるという問題が発生した場合は、次のアプローチを検討してください。1.コン...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開

Java で JComponent が背景画像の後ろに隠れるのはなぜですか?背景画像で隠された JComponent のデバッグJava アプリケーションで JLabel などの JComponent を操作する場合、適切な動作を保証することが重要です。そして視認性。コンポーネントが背景画像の背後に隠れるという問題が発生した場合は、次のアプローチを検討してください。1.コン...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開 -

PHP であらゆるタイプのスマート クォートを変換するには?PHP ですべての種類のスマート引用符を変換するスマート引用符は、通常の直線引用符 (' と ") の代わりに使用される活字記号です。ただし、ソフトウェア アプリケーションでは、さまざまな種類のスマート クオート間の変換に苦労することがよくあります。 スマート クォート変換の課題ス...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開

PHP であらゆるタイプのスマート クォートを変換するには?PHP ですべての種類のスマート引用符を変換するスマート引用符は、通常の直線引用符 (' と ") の代わりに使用される活字記号です。ただし、ソフトウェア アプリケーションでは、さまざまな種類のスマート クオート間の変換に苦労することがよくあります。 スマート クォート変換の課題ス...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開 -

JavaScript 配列をループするさまざまな方法には何がありますか?JavaScript を使用した配列のループ配列の要素の反復処理は、JavaScript の一般的なタスクです。利用可能なアプローチはいくつかありますが、それぞれに独自の長所と制限があります。これらのオプションを見てみましょう:配列1. for-of ループ (ES2015 )このループは、反復子を...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開

JavaScript 配列をループするさまざまな方法には何がありますか?JavaScript を使用した配列のループ配列の要素の反復処理は、JavaScript の一般的なタスクです。利用可能なアプローチはいくつかありますが、それぞれに独自の長所と制限があります。これらのオプションを見てみましょう:配列1. for-of ループ (ES2015 )このループは、反復子を...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開 -

Python で Selenium WebDriver の実行を効率的に一時停止するにはどうすればよいですか?Selenium WebDriver の待機ステートメントと条件ステートメント質問: Python で Selenium WebDriver の実行をミリ秒間一時停止するにはどうすればよいですか?答え:その間time.sleep() 関数は、指定した秒数の間実行を一時停止するために使用できますが、S...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開

Python で Selenium WebDriver の実行を効率的に一時停止するにはどうすればよいですか?Selenium WebDriver の待機ステートメントと条件ステートメント質問: Python で Selenium WebDriver の実行をミリ秒間一時停止するにはどうすればよいですか?答え:その間time.sleep() 関数は、指定した秒数の間実行を一時停止するために使用できますが、S...プログラミング 2024 年 12 月 26 日に公開

中国語を勉強する

- 1 「歩く」は中国語で何と言いますか? 走路 中国語の発音、走路 中国語学習

- 2 「飛行機に乗る」は中国語で何と言いますか? 坐飞机 中国語の発音、坐飞机 中国語学習

- 3 「電車に乗る」は中国語で何と言いますか? 坐火车 中国語の発音、坐火车 中国語学習

- 4 「バスに乗る」は中国語で何と言いますか? 坐车 中国語の発音、坐车 中国語学習

- 5 中国語でドライブは何と言うでしょう? 开车 中国語の発音、开车 中国語学習

- 6 水泳は中国語で何と言うでしょう? 游泳 中国語の発音、游泳 中国語学習

- 7 中国語で自転車に乗るってなんて言うの? 骑自行车 中国語の発音、骑自行车 中国語学習

- 8 中国語で挨拶はなんて言うの? 你好中国語の発音、你好中国語学習

- 9 中国語でありがとうってなんて言うの? 谢谢中国語の発音、谢谢中国語学習

- 10 How to say goodbye in Chinese? 再见Chinese pronunciation, 再见Chinese learning