Java Cleaners:管理外部資源的現代方法

Code for this article can be found on GitHub.

If you’re the type of programmer who likes to understand the internals of how things work before seeing examples,

you can jump directly to Cleaners behind the scene after the introduction.

- Introduction

- Simple Cleaner in action

- Cleaners, the right way

- Cleaners, the effective way

- Cleaners behind the scene

Introduction

Think of a scenario where you have an object that holds references to external resources (files, sockets, and so on). And you want to have control over how these resources are released once the holding object is no longer active/accessible, how do you achieve that in Java?. Prior to Java 9 programmers could use a finalizer by overriding the Object’s class finalize() method. Finalizers have many disadvantages, including being slow, unreliable and dangerous. It is one of those features that are hated by both those who implement the JDK and those who use it.

Since Java 9, Finalizers have been deprecated and programmers have a better option to achieve this in Cleaners, Cleaners provide a better way to manage and handle cleaning/finalizing actions. Cleaners work in a pattern where they let resource holding objects register themselves and their corresponding cleaning actions. And then Cleaners will call the cleaning actions once these objects are not accessible by the application code.

This is not the article to tell you why Cleaners are better than Finalizers, though I will briefly list some of their differences.

Finalizers Vs Cleaners

| Finalizers | Cleaners |

|---|---|

| Finalizers are invoked by one of Garbage Collector’s threads, you as a programmer don’t have control over what thread will invoke your finalizing logic | Unlike with finalizers, with Cleaners, programmers can opt to have control over the thread that invokes the cleaning logic. |

| Finalizing logic is invoked when the object is actually being collected by GC | Cleaning logic is invoked when the object becomes Phantom Reachable, that is our application has no means to access it anymore |

| Finalizing logic is part of the object holding the resources | Cleaning logic and its state are encapsulated in a separate object. |

| No registration/deregistration mechanism | Provides means for registering cleaning actions and explicit invocation/deregistration |

Simple Cleaner in action

Enough chit-chats let us see Cleaners in action.

ResourceHolder

import java.lang.ref.Cleaner;

public class ResourceHolder {

private static final Cleaner CLEANER = Cleaner.create();

public ResourceHolder() {

CLEANER.register(this, () -> System.out.println("I'm doing some clean up"));

}

public static void main(String... args) {

ResourceHolder resourceHolder = new ResourceHolder();

resourceHolder = null;

System.gc();

}}

Few lines of code but a lot is happening here, Let us break it down

- The constant CLEANER is of type java.lang.ref.Cleaner, as you can tell from its name, this is the central and starting point of the Cleaners feature in Java. The CLEANER variable is declared as static as it should be, Cleaners should never be instance variables, they should be shared across different classes as much as possible.

- In the constructor, instances of ResourceHolder are registering themselves to the Cleaner along with their cleaning action, the cleaning action is a Runnable job that the Cleaner guarantees to invoke at most once (at most once, meaning it is possible not to run at all).

By calling Cleaner’s register() method, these instances are basically saying two things to the Cleaner

- Keep track of me as long as I live

- And once I am no longer active (Phantom Reachable), please do your best and invoke my cleaning action.

- In the main method we instantiate an object of ResourceHolder and immediately set its variable to null, since the object has only one variable reference, our application can no longer access the object, i.e., it has become Phantom Reachable

- We call System.gc() to request JVM to run the Garbage Collector, consequentially this will trigger the Cleaner to run the cleaning action. Typically, you don’t need to call System.gc() but as simple as our application, we need to facilitate the Cleaner to run the action

Run the application, and hopefully you see I’m doing some clean up somewhere in your standard output.

? CAUTION

We started with the simplest possible way to use Cleaners, so we can demonstrate its usage in a simplified way, bear in mind though this is neither effective nor the right way to use Cleaners

Cleaners, the right way

Our first example was more than good enough to see Cleaners in action,

but as we warned, it is not the right way to use Cleaners in a real application.

Let’s see what is wrong with what we did.

-

We initiated a Cleaner object as a class member of the ResourceHolder: As we mentioned earlier Cleaners should be shared across Classes and should not belong to individual classes, reason behind being each Cleaner instance maintains a thread, which is a limited native resource, and you want to be cautious when you consume native resources.

In a real application, we typically get a Cleaner object from a utility or a Singleton class like

private static CLEANER = AppUtil.getCleaner();

-

We passed in a lambda as our Cleaning action: You should NEVER pass in a lambda as your cleaning action.

To understand why,

let us refactor our previous example by extracting the printed out message and make it an instance variableResourceHolder

public class ResourceHolder { private static final Cleaner CLEANER = Cleaner.create(); private final String cleaningMessage = "I'm doing some clean up"; public ResourceHolder() { CLEANER.register(this, () -> System.out.println(cleaningMessage)); } }Run the application and see what happens.

I will tell you what happens,

the cleaning action will never get invoked no matter how many times you run your application.

Let us see why- Internally, Cleaners make use of PhantomReference and ReferenceQueue to keep track of registered objects, once an object becomes Phantom Reachable the ReferenceQueue will notify the Cleaner and the Cleaner will use its thread to run the corresponding cleaning action.

- By having the lambda accessing the instance member we’re forcing the lambda to hold the this reference(of ResourceHolder instance), because of this the object will never ever become Phantom Reachable because our Application code still has reference to it.

? NOTE

If you still wonder how in our first example, the cleaning action is invoked despite having it as a lambda. The reason is, the lambda in the first example does not access any instance variable, and unlike inner classes, Lambdas won’t implicitly hold the containing object reference unless they’re forced to.

The right way is to encapsulate your cleaning action together with the state it needs in a static nested class.

? Warning

Don’t use inner class anonymous or not, it is worse than using lambda because an inner class instance would hold a reference to the outer class instance regardless of whether they access their instance variable or not. We didn't make use of the return value from the Cleaner.create(): The create() actually returns something very important.a Cleanable object, this object has a clean() method that wraps your cleaning logic, you as a programmer can opt to do the cleanup yourself by invoking the clean() method. As mentioned earlier, another thing that makes Cleaners superior to Finalizers is that you can actually deregister your cleaning action. The clean() method actually deregisters your object first, and then it invokes your cleaning action, this way it guarantees the at-most once behavior.

Now let us improve each one of these points and revise our ResourceHolder class

ResourceHolder

import java.lang.ref.Cleaner;

public class ResourceHolder {

private final Cleaner.Cleanable cleanable;

private final ExternalResource externalResource;

public ResourceHolder(ExternalResource externalResource) {

cleanable = AppUtil.getCleaner().register(this, new CleaningAction(externalResource));

this.externalResource = externalResource;

}

// You can call this method whenever is the right time to release resource

public void releaseResource() {

cleanable.clean();

}

public void doSomethingWithResource() {

System.out.printf("Do something cool with the important resource: %s \n", this.externalResource);

}

static class CleaningAction implements Runnable {

private ExternalResource externalResource;

CleaningAction(ExternalResource externalResource) {

this.externalResource = externalResource;

}

@Override

public void run() {

// Cleaning up the important resources

System.out.println("Doing some cleaning logic here, releasing up very important resource");

externalResource = null;

}

}

public static void main(String... args) {

ResourceHolder resourceHolder = new ResourceHolder(new ExternalResource());

resourceHolder.doSomethingWithResource();

/*

After doing some important work, we can explicitly release

resources/invoke the cleaning action

*/

resourceHolder.releaseResource();

// What if we explicitly invoke the cleaning action twice?

resourceHolder.releaseResource();

}

}

ExternalResource is our hypothetical resource that we want to release when we’re done with it.

The cleaning action is now encapsulated in its own class, and we make use of the CleaniangAction object, we call it’s clean() method in the releaseResources() method to do the cleanup ourselves.

As stated earlier, Cleaners guarantee at most one invocation of the cleaning action, and since we call the clean() method explicitly the Cleaner will not invoke our cleaning action except in the case of a failure like an exception is thrown before the clean method is called, in this case the Cleaner will invoke our cleaning action when the ResourceHolder object becomes Phantom Reachable, that is we use the Cleaner as our safety-net, our backup plan when the first plan to clean our own mess doesn’t work.

❗ IMPORTANT

The behavior of Cleaners during System.exit is implementation-specific. With this in mind, programmers should always prefer to explicitly invoke the cleaning action over relying on the Cleaners themselves..

Cleaners, the effective way

By now we’ve established the right way to use Cleaners is to explicitly call the cleaning action and rely on them as our backup plan.What if there’s a better way? Where we don’t explicitly call the cleaning action, and the Cleaner stays intact as our safety-net.

This can be achieved by having the ResourceHolder class implement the AutoCloseable interface and place the cleaning action call in the close() method, our ResourceHolder can now be used in a try-with-resources block. The revised ResourceHolder should look like below.

ResourceHolder

import java.lang.ref.Cleaner.Cleanable;

public class ResourceHolder implements AutoCloseable {

private final ExternalResource externalResource;

private final Cleaner.Cleanable cleanable;

public ResourceHolder(ExternalResource externalResource) {

this.externalResource = externalResource;

cleanable = AppUtil.getCleaner().register(this, new CleaningAction(externalResource));

}

public void doSomethingWithResource() {

System.out.printf("Do something cool with the important resource: %s \n", this.externalResource);

}

@Override

public void close() {

System.out.println("cleaning action invoked by the close method");

cleanable.clean();

}

static class CleaningAction implements Runnable {

private ExternalResource externalResource;

CleaningAction(ExternalResource externalResource) {

this.externalResource = externalResource;

}

@Override

public void run() {

// cleaning up the important resources

System.out.println("Doing some cleaning logic here, releasing up very important resources");

externalResource = null;

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

// This is an effective way to use cleaners with instances that hold crucial resources

try (ResourceHolder resourceHolder = new ResourceHolder(new ExternalResource(1))) {

resourceHolder.doSomethingWithResource();

System.out.println("Goodbye");

}

/*

In case the client code does not use the try-with-resource as expected,

the Cleaner will act as the safety-net

*/

ResourceHolder resourceHolder = new ResourceHolder(new ExternalResource(2));

resourceHolder.doSomethingWithResource();

resourceHolder = null;

System.gc(); // to facilitate the running of the cleaning action

}

}

Cleaners behind the scene

? NOTE

To understand more and see how Cleaners work, checkout the OurCleaner class under the our_cleaner package that imitates the JDK real implementation of Cleaner. You can replace the real Cleaner and Cleanable with OurCleaner and OurCleanable respectively in all of our examples and play with it.

Let us first get a clearer picture of a few, already mentioned terms, phantom-reachable, PhantomReference and ReferenceQueue

-

Consider the following code

Object myObject = new Object();

In the Garbage Collector (GC) world the created instance of Object is said to be strongly-reachable, why? Because it is alive, and in-use i.e., Our application code has a reference to it that is stored in the myObject variable, assume we don’t set another variable and somewhere in our code this happens

myObject = null;

The instance is now said to be unreachable, and is eligible for reclamation by the GC.

Now let us tweak the code a bit

Object myObject = new Object(); PhantomReference

Reference is a class provided by JDK to represent reachability of an object during JVM runtime, the object a Reference object is referring to is known as referent, PhantomReference is a type(also an extension) of Reference whose purpose will be explained below in conjunction with ReferenceQueue.

Ignore the second parameter of the constructor for now, and again assume somewhere in our code this happens again

myObject = null;

Now our object is not just unreachable it is phantom-reachable because no part of our application code can access it, AND it is a referent of a PhantomReference object.

-

After the GC has finalized a phantom-reachable object, the GC attaches its PhantomReference object(not the referent) to a special kind of queue called ReferenceQueue. Let us see how these two concepts work together

Object myObject = new Object(); ReferenceQueue

We supply a ReferenceQueue when we create a PhantomReference object so the GC knows where to attach it when its referent has been finalized. The ReferenceQueue class provides two methods to poll the queue, remove(), this will block when the queue is empty until the queue has an element to return, and poll() this is non-blocking, when the queue is empty it will return null immediately.

With that explanation, the code above should be easy to understand, once myObject becomes phantom-reachable the GC will attach the PhantomReference object to queue and we get it by using the remove() method, that is to say reference1 and reference2 variables refer to the same object.

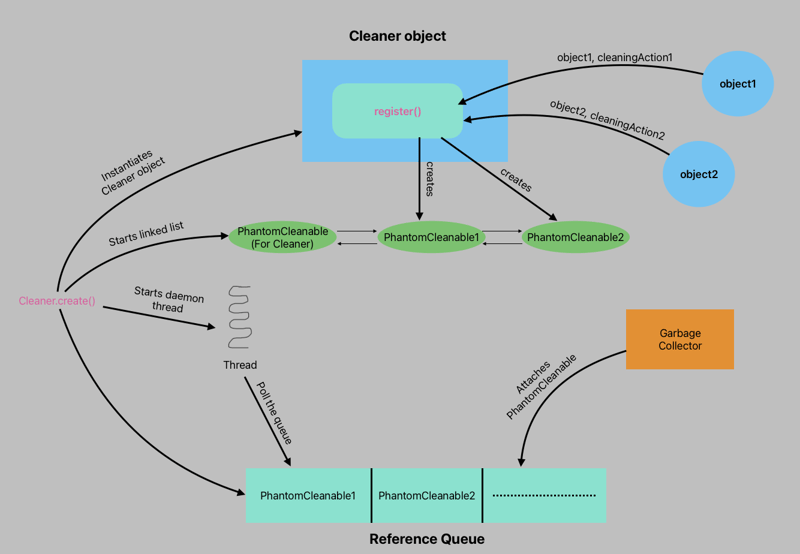

Now that these concepts are out of the way, let’s explain two Cleaner-specific types

- For each cleaning action, Cleaner will wrap it in a Cleanable instance, Cleanable has one method, clean(), this method ensure the at-most once invocation behavior before invoking the cleaning action.

- PhantomCleanable implements Cleanable and extends PhantomReference, this class is the Cleaner’s way to associate the referent(resource holder) with their cleaning action

From this point on understanding the internals of Cleaner should be straight forward.

Cleaner Life-Cycle Overview

Let us look at the life-cycle of a Cleaner object

-

The static Cleaner.create() method instantiates a new Cleaner but it also does a few other things

- It instantiates a new ReferenceQueue, that the Cleaner objet’s thread will be polling

- It creates a doubly linked list of PhantomCleanable objects, these objects are associated with the queue created from the previous step.

- It creates a PhantomCleanable object with itself as the referent and empty cleaning action.

- It starts a daemon thread that will be polling the ReferenceQueue as long as the doubly linked list is not empty.

By adding itself into the list, the cleaner ensures that its thread runs at least until the cleaner itself becomes unreachable

For each Cleaner.register() call, the cleaner creates an instance of PhantomCleanable with the resource holder as the referent and the cleaning action will be wrapped in the clean() method, the object is then added to the aforementioned linked list.

The Cleaner’s thread will be polling the queue, and when a PhantomCleanable is returned by the queue, it will invoke its clean() method. Remember the clean() method only calls the cleaning action if it manages to remove the PhantomCleanable object from the linked list, if the PhantomCleanable object is not on the linked list it does nothing

-

The thread will continue to run as long as the linked list is not empty, this will only happen when

- All the cleaning actions have been invoked, and

- The Cleaner itself has become phantom-reachable and has been reclaimed by the GC

-

Android如何向PHP服務器發送POST數據?在android apache httpclient(已棄用) httpclient httpclient = new defaulthttpclient(); httppost httppost = new httppost(“ http://www.yoursite.com/script.p...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

Android如何向PHP服務器發送POST數據?在android apache httpclient(已棄用) httpclient httpclient = new defaulthttpclient(); httppost httppost = new httppost(“ http://www.yoursite.com/script.p...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

同實例無需轉儲複製MySQL數據庫方法在同一實例上複製一個MySQL數據庫而無需轉儲在同一mySQL實例上複製數據庫,而無需創建InterMediate sqql script。以下方法為傳統的轉儲和IMPORT過程提供了更簡單的替代方法。 直接管道數據 MySQL手動概述了一種允許將mysqldump直接輸出到MySQL cli...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

同實例無需轉儲複製MySQL數據庫方法在同一實例上複製一個MySQL數據庫而無需轉儲在同一mySQL實例上複製數據庫,而無需創建InterMediate sqql script。以下方法為傳統的轉儲和IMPORT過程提供了更簡單的替代方法。 直接管道數據 MySQL手動概述了一種允許將mysqldump直接輸出到MySQL cli...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

FastAPI自定義404頁面創建指南response = await call_next(request) if response.status_code == 404: return RedirectResponse("https://fastapi.tiangolo.com") else: ...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

FastAPI自定義404頁面創建指南response = await call_next(request) if response.status_code == 404: return RedirectResponse("https://fastapi.tiangolo.com") else: ...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

Go web應用何時關閉數據庫連接?在GO Web Applications中管理數據庫連接很少,考慮以下簡化的web應用程序代碼:出現的問題:何時應在DB連接上調用Close()方法? ,該特定方案將自動關閉程序時,該程序將在EXITS EXITS EXITS出現時自動關閉。但是,其他考慮因素可能保證手動處理。 選項1:隱式關閉終...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

Go web應用何時關閉數據庫連接?在GO Web Applications中管理數據庫連接很少,考慮以下簡化的web應用程序代碼:出現的問題:何時應在DB連接上調用Close()方法? ,該特定方案將自動關閉程序時,該程序將在EXITS EXITS EXITS出現時自動關閉。但是,其他考慮因素可能保證手動處理。 選項1:隱式關閉終...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

為什麼儘管有效代碼,為什麼在PHP中捕獲輸入?在php ;?>" method="post">The intention is to capture the input from the text box and display it when the submit button is clicked.但是,輸出...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

為什麼儘管有效代碼,為什麼在PHP中捕獲輸入?在php ;?>" method="post">The intention is to capture the input from the text box and display it when the submit button is clicked.但是,輸出...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

在UTF8 MySQL表中正確將Latin1字符轉換為UTF8的方法在UTF8表中將latin1字符轉換為utf8 ,您遇到了一個問題,其中含義的字符(例如,“jáuòiñe”)在utf8 table tabled tablesset中被extect(例如,“致電。為了解決此問題,您正在嘗試使用“ mb_convert_encoding”和“ iconv”轉換受...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

在UTF8 MySQL表中正確將Latin1字符轉換為UTF8的方法在UTF8表中將latin1字符轉換為utf8 ,您遇到了一個問題,其中含義的字符(例如,“jáuòiñe”)在utf8 table tabled tablesset中被extect(例如,“致電。為了解決此問題,您正在嘗試使用“ mb_convert_encoding”和“ iconv”轉換受...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

在Pandas中如何將年份和季度列合併為一個週期列?pandas data frame thing commans date lay neal and pree pree'和pree pree pree”,季度 2000 q2 這個目標是通過組合“年度”和“季度”列來創建一個新列,以獲取以下結果: [python中的concate...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

在Pandas中如何將年份和季度列合併為一個週期列?pandas data frame thing commans date lay neal and pree pree'和pree pree pree”,季度 2000 q2 這個目標是通過組合“年度”和“季度”列來創建一個新列,以獲取以下結果: [python中的concate...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

如何正確使用與PDO參數的查詢一樣?在pdo 中使用類似QUERIES在PDO中的Queries時,您可能會遇到類似疑問中描述的問題:此查詢也可能不會返回結果,即使$ var1和$ var2包含有效的搜索詞。錯誤在於不正確包含%符號。 通過將變量包含在$ params數組中的%符號中,您確保將%字符正確替換到查詢中。沒有此修改,PD...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

如何正確使用與PDO參數的查詢一樣?在pdo 中使用類似QUERIES在PDO中的Queries時,您可能會遇到類似疑問中描述的問題:此查詢也可能不會返回結果,即使$ var1和$ var2包含有效的搜索詞。錯誤在於不正確包含%符號。 通過將變量包含在$ params數組中的%符號中,您確保將%字符正確替換到查詢中。沒有此修改,PD...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

如何限制動態大小的父元素中元素的滾動範圍?在交互式接口中實現垂直滾動元素的CSS高度限制問題:考慮一個佈局,其中我們具有與用戶垂直滾動一起移動的可滾動地圖div,同時與固定的固定sidebar保持一致。但是,地圖的滾動無限期擴展,超過了視口的高度,阻止用戶訪問頁面頁腳。 $("#map").css({ margin...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

如何限制動態大小的父元素中元素的滾動範圍?在交互式接口中實現垂直滾動元素的CSS高度限制問題:考慮一個佈局,其中我們具有與用戶垂直滾動一起移動的可滾動地圖div,同時與固定的固定sidebar保持一致。但是,地圖的滾動無限期擴展,超過了視口的高度,阻止用戶訪問頁面頁腳。 $("#map").css({ margin...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

為什麼我在Silverlight Linq查詢中獲得“無法找到查詢模式的實現”錯誤?查詢模式實現缺失:解決“無法找到”錯誤在銀光應用程序中,嘗試使用LINQ建立錯誤的數據庫連接的嘗試,無法找到以查詢模式的實現。 ”當省略LINQ名稱空間或查詢類型缺少IEnumerable 實現時,通常會發生此錯誤。 解決問題來驗證該類型的質量是至關重要的。在此特定實例中,tblpersoon可能...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

為什麼我在Silverlight Linq查詢中獲得“無法找到查詢模式的實現”錯誤?查詢模式實現缺失:解決“無法找到”錯誤在銀光應用程序中,嘗試使用LINQ建立錯誤的數據庫連接的嘗試,無法找到以查詢模式的實現。 ”當省略LINQ名稱空間或查詢類型缺少IEnumerable 實現時,通常會發生此錯誤。 解決問題來驗證該類型的質量是至關重要的。在此特定實例中,tblpersoon可能...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

Java中如何使用觀察者模式實現自定義事件?在Java 中創建自定義事件的自定義事件在許多編程場景中都是無關緊要的,使組件能夠基於特定的觸發器相互通信。本文旨在解決以下內容:問題語句我們如何在Java中實現自定義事件以促進基於特定事件的對象之間的交互,定義了管理訂閱者的類界面。 以下代碼片段演示瞭如何使用觀察者模式創建自定義事件: args...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

Java中如何使用觀察者模式實現自定義事件?在Java 中創建自定義事件的自定義事件在許多編程場景中都是無關緊要的,使組件能夠基於特定的觸發器相互通信。本文旨在解決以下內容:問題語句我們如何在Java中實現自定義事件以促進基於特定事件的對象之間的交互,定義了管理訂閱者的類界面。 以下代碼片段演示瞭如何使用觀察者模式創建自定義事件: args...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

如何簡化PHP中的JSON解析以獲取多維陣列?php 試圖在PHP中解析JSON數據的JSON可能具有挑戰性,尤其是在處理多維數組時。要簡化過程,建議將JSON作為數組而不是對象解析。 執行此操作,將JSON_DECODE函數與第二個參數設置為true:[&&&&& && &&&&& json = JSON = JSON_DECODE($ ...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

如何簡化PHP中的JSON解析以獲取多維陣列?php 試圖在PHP中解析JSON數據的JSON可能具有挑戰性,尤其是在處理多維數組時。要簡化過程,建議將JSON作為數組而不是對象解析。 執行此操作,將JSON_DECODE函數與第二個參數設置為true:[&&&&& && &&&&& json = JSON = JSON_DECODE($ ...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

反射動態實現Go接口用於RPC方法探索在GO 使用反射來實現定義RPC式方法的界面。例如,考慮一個接口,例如:鍵入myService接口{ 登錄(用戶名,密碼字符串)(sessionId int,錯誤錯誤) helloworld(sessionid int)(hi String,錯誤錯誤) } 替代方案而不是依靠反射...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

反射動態實現Go接口用於RPC方法探索在GO 使用反射來實現定義RPC式方法的界面。例如,考慮一個接口,例如:鍵入myService接口{ 登錄(用戶名,密碼字符串)(sessionId int,錯誤錯誤) helloworld(sessionid int)(hi String,錯誤錯誤) } 替代方案而不是依靠反射...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

為什麼我會收到MySQL錯誤#1089:錯誤的前綴密鑰?mySQL錯誤#1089:錯誤的前綴鍵錯誤descript [#1089-不正確的前綴鍵在嘗試在表中創建一個prefix鍵時會出現。前綴鍵旨在索引字符串列的特定前綴長度長度,可以更快地搜索這些前綴。 了解prefix keys `這將在整個Movie_ID列上創建標準主鍵。主密鑰對於唯一識...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

為什麼我會收到MySQL錯誤#1089:錯誤的前綴密鑰?mySQL錯誤#1089:錯誤的前綴鍵錯誤descript [#1089-不正確的前綴鍵在嘗試在表中創建一個prefix鍵時會出現。前綴鍵旨在索引字符串列的特定前綴長度長度,可以更快地搜索這些前綴。 了解prefix keys `這將在整個Movie_ID列上創建標準主鍵。主密鑰對於唯一識...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05 -

C++20 Consteval函數中模板參數能否依賴於函數參數?[ consteval函數和模板參數依賴於函數參數在C 17中,模板參數不能依賴一個函數參數,因為編譯器仍然需要對非contexexpr futcoriations contim at contexpr function進行評估。 compile time。 C 20引入恆定函數,必須在編譯時進...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

C++20 Consteval函數中模板參數能否依賴於函數參數?[ consteval函數和模板參數依賴於函數參數在C 17中,模板參數不能依賴一個函數參數,因為編譯器仍然需要對非contexexpr futcoriations contim at contexpr function進行評估。 compile time。 C 20引入恆定函數,必須在編譯時進...程式設計 發佈於2025-07-05

學習中文

- 1 走路用中文怎麼說? 走路中文發音,走路中文學習

- 2 坐飛機用中文怎麼說? 坐飞机中文發音,坐飞机中文學習

- 3 坐火車用中文怎麼說? 坐火车中文發音,坐火车中文學習

- 4 坐車用中文怎麼說? 坐车中文發音,坐车中文學習

- 5 開車用中文怎麼說? 开车中文發音,开车中文學習

- 6 游泳用中文怎麼說? 游泳中文發音,游泳中文學習

- 7 騎自行車用中文怎麼說? 骑自行车中文發音,骑自行车中文學習

- 8 你好用中文怎麼說? 你好中文發音,你好中文學習

- 9 謝謝用中文怎麼說? 谢谢中文發音,谢谢中文學習

- 10 How to say goodbye in Chinese? 再见Chinese pronunciation, 再见Chinese learning