技術面接の質問 - パート タイプスクリプト

Introduction

Hello, hello!! :D

Hope you’re all doing well!

How we’re really feeling:

I’m back with the second part of this series. ?

In this chapter, we’ll dive into the ✨Typescript✨ questions I’ve faced during interviews.

I’ll keep the intro short, so let’s jump right in!

## Questions

1. What are generics in typescript? What is

2. What are the differences between interfaces and types?

3. What are the differences between any, null, unknown, and never?

Question 1: What are generics in typescript? What is ?

The short answer is...

Generics in TypeScript allow us to create reusable functions, classes, and interfaces that can work with a variety of types, without having to specify a particular one. This helps to avoid using any as a catch-all type.

The syntax

is used to declare a generic type, but you could also use , , or any other placeholder.

How does it work?

Let’s break it down with an example.

Suppose I have a function that accepts a parameter and returns an element of the same type. If I write that function with a specific type, it would look like this:

function returnElement(element: string): string {

return element;

}

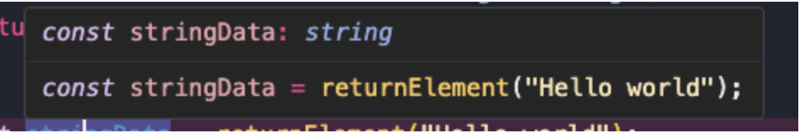

const stringData = returnElement("Hello world");

I know the type of stringData will be “string” because I declared it.

But what happens if I want to return a different type?

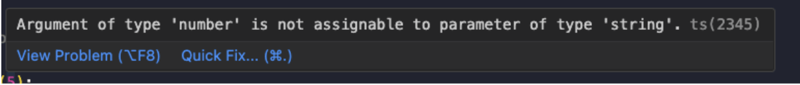

const numberData = returnElement(5);

I will receive an error message because the type differs from what was declared.

The solution could be to create a new function to return a number type.

function returnNumber(element: number): number {

return element;

}

That approach would work, but it could lead to duplicated code.

A common mistake to avoid this is using any instead of a declared type, but that defeats the purpose of type safety.

function returnElement2(element: any): any {

return element;

}

However, using any causes us to lose the type safety and error detection feature that Typescript has.

Also, if you start using any whenever you need to avoid duplicate code, your code will lose maintainability.

This is precisely when it’s beneficial to use generics.

function returnGenericElement(element: T): T { return element; }

The function will receive an element of a specific type; that type will replace the generic and remain so throughout the runtime.

This approach enables us to eliminate duplicated code while preserving type safety.

const stringData2 = returnGenericElement("Hello world");

const numberData2 = returnGenericElement(5);

But what if I need a specific function that comes from an array?

We could declare the generic as an array and write it like this:

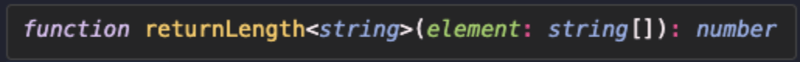

function returnLength(element: T[]): number { return element.length; }

Then,

const stringLength = returnLength(["Hello", "world"]);

The declared types will be replaced by the type provided as a parameter.

We can also use generics in classes.

class Addition {

add: (x: U, y: U) => U;

}

I have three points to make about this code:

- add is an anonymous arrow function (which I discussed in the first chapter).

- The generic can be named ,

, or even , if you prefer. - Since we haven't specified the type yet, we can't implement operations inside the classes. Therefore, we need to instantiate the class by declaring the type of the generic and then implement the function.

Here’s how it looks:

const operation = new Addition(); operation.add = (x, y) => x y; => We implement the function here console.log(operation.add(5, 6)); // 11

And, one last thing to add before ending this question.

Remember that generics are a feature of Typescript. That means the generics will be erased when we compile it into Javascript.

From

function returnGenericElement(element: T): T { return element; }

to

function returnGenericElement(element) {

return element;

}

Question 2: What are the differences between interfaces and types?

The short answer is:

- Declaration merging works with interfaces but not with types.

- You cannot use implements in a class with union types.

- You cannot use extends with an interface using union types.

Regarding the first point, what do I mean by declaration merging?

Let me show you:

I’ve defined the same interface twice while using it in a class. The class will then incorporate the properties declared in both definitions.

interface CatInterface {

name: string;

age: number;

}

interface CatInterface {

color: string;

}

const cat: CatInterface = {

name: "Tom",

age: 5,

color: "Black",

};

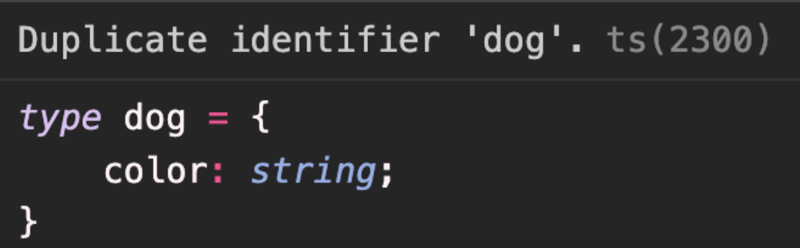

This does not occur with types. If we attempt to define a type more than once, TypeScript will throw an error.

type dog = {

name: string;

age: number;

};

type dog = { // Duplicate identifier 'dog'.ts(2300)

color: string;

};

const dog1: dog = {

name: "Tom",

age: 5,

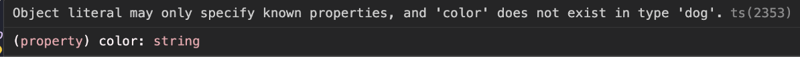

color: "Black", //Object literal may only specify known properties, and 'color' does not exist in type 'dog'.ts(2353)

};

Regarding the following points, let’s differentiate between union and intersection types:

Union types allow us to specify that a value can be one of several types. This is useful when a variable can hold multiple types.

Intersection types allow us to combine types into one. It is defined using the & operator.

type cat = {

name: string;

age: number;

};

type dog = {

name: string;

age: number;

breed: string;

};

Union type:

type animal = cat | dog;

Intersection type:

type intersectionAnimal = cat & dog;

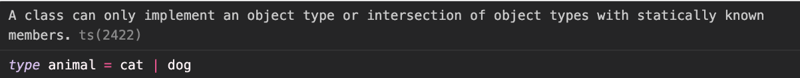

If we attempt to use the implements keyword with a union type, such as Animal, TypeScript will throw an error. This is because implements expects a single interface or type, rather than a union type.

class pet implements animal{

name: string;

age: number;

breed: string;

constructor(name: string, age: number, breed: string){

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.breed = breed;

}

}

Typescript allows us to use “implements” with:

a. Intersection types

class pet2 implements intersectionAnimal {

name: string;

age: number;

color: string;

breed: string;

constructor(name: string, age: number, color: string, breed: string) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.color = color;

this.breed = breed;

}

}

b. Interfaces

interface CatInterface {

name: string;

age: number;

color: string;

}

class pet3 implements CatInterface {

name: string;

age: number;

color: string;

constructor(name: string, age: number, color: string) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.color = color;

}

}

c. Single Type.

class pet4 implements cat {

name: string;

age: number;

color: string;

constructor(name: string, age: number, color: string) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

this.color = color;

}

}

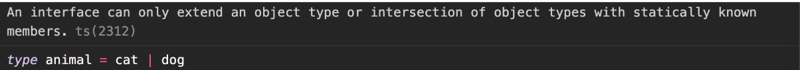

The same issue occurs when we try to use extends with a union type. TypeScript will throw an error because an interface cannot extend a union type. Here’s an example

interface petUnionType extends animal {

name: string;

age: number;

breed: string;

}

You cannot extend a union type because it represents multiple possible types, and it's unclear which type's properties should be inherited.

BUT you can extend a type or an interface.

interface petIntersectionType extends intersectionAnimal {

name: string;

age: number;

color: string;

breed: string;

}

interface petCatInterface extends CatInterface {

name: string;

age: number;

color: string;

}

Also, you can extend a single type.

interface petCatType extends cat {

name: string;

age: number;

color: string;

}

Question 3: What are the differences between any, null, unknown, and never?

Short answer:

Any => It’s a top-type variable (also called universal type or universal supertype). When we use any in a variable, the variable could hold any type. It's typically used when the specific type of a variable is unknown or expected to change. However, using any is not considered a best practice; it’s recommended to use generics instead.

let anyVariable: any;

While any allows for operations like calling methods, the TypeScript compiler won’t catch errors at this stage. For instance:

anyVariable.trim(); anyVariable.length;

You can assign any value to an any variable:

anyVariable = 5; anyVariable = "Hello";

Furthermore, you can assign an any variable to another variable with a defined type:

let booleanVariable: boolean = anyVariable; let numberVariable: number = anyVariable;

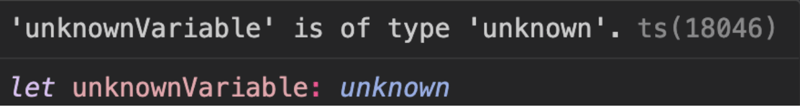

Unknown => This type, like any, could hold any value and is also considered the top type. We use it when we don’t know the variable type, but it will be assigned later and remain the same during the runtime. Unknow is a less permissive type than any.

let unknownVariable: unknown;

Directly calling methods on unknown will result in a compile-time error:

unknownVariable.trim(); unknownVariable.length;

Before using it, we should perform checks like:

if (typeof unknownVariable === "string") {

unknownVariable.trim();

}

Like any, we could assign any type to the variable.

unknownVariable = 5; unknownVariable = "Hello";

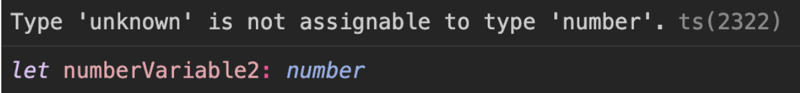

However, we cannot assign the unknown type to another type, but any or unknown.

let booleanVariable2: boolean = unknownVariable; let numberVariable2: number = unknownVariable;

This will show us an error

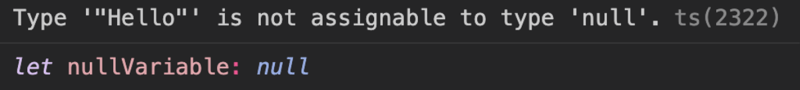

Null => The variable can hold either type. It means that the variable does not have a value.

let nullVariable: null; nullVariable = null;

Attempting to assign any other type to a null variable will result in an error:

nullVariable = "Hello";

Never => We use this type to specify that a function doesn’t have a return value.

function throwError(message: string): never {

throw new Error(message);

}

function infiniteLoop(): never {

while (true) {

console.log("Hello");

}

}

The end...

We finish with Typescript,

For today (?

I hope this was helpful to someone.

If you have any technical interview questions you'd like me to explain, feel free to let me know in the comments. ??

Have a great week ?

-

PDOパラメーターを使用してクエリのように正しく使用する方法は?を使用してpdo PDOで同様のクエリを実装しようとすると、以下のクエリのような問題に遭遇する可能性があります: $query = "SELECT * FROM tbl WHERE address LIKE '%?%' OR address LIKE '%?%'";...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

PDOパラメーターを使用してクエリのように正しく使用する方法は?を使用してpdo PDOで同様のクエリを実装しようとすると、以下のクエリのような問題に遭遇する可能性があります: $query = "SELECT * FROM tbl WHERE address LIKE '%?%' OR address LIKE '%?%'";...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

PHPを使用してBlob(画像)をMySQLに適切に挿入する方法は?php mysqlデータベースを持つmysqlデータベースにブロブを挿入すると、mysqlデータベースに画像を保存しようとすると、遭遇するかもしれません問題。このガイドは、画像データを正常に保存するためのソリューションを提供します。 ImageId、image) values( &...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

PHPを使用してBlob(画像)をMySQLに適切に挿入する方法は?php mysqlデータベースを持つmysqlデータベースにブロブを挿入すると、mysqlデータベースに画像を保存しようとすると、遭遇するかもしれません問題。このガイドは、画像データを正常に保存するためのソリューションを提供します。 ImageId、image) values( &...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

ポイントインポリゴン検出により効率的な方法:Ray TracingまたはMatplotlib \ 's path.contains_points?Pythonの効率的なポイントインポリゴン検出 ポリゴン内にあるかどうかを決定することは、計算ジオメトリの頻繁なタスクです。このタスクの効率的な方法を見つけることは、多数のポイントを評価する場合に有利です。ここでは、一般的に使用される2つの方法を調査して比較します:Ray TracingとM...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

ポイントインポリゴン検出により効率的な方法:Ray TracingまたはMatplotlib \ 's path.contains_points?Pythonの効率的なポイントインポリゴン検出 ポリゴン内にあるかどうかを決定することは、計算ジオメトリの頻繁なタスクです。このタスクの効率的な方法を見つけることは、多数のポイントを評価する場合に有利です。ここでは、一般的に使用される2つの方法を調査して比較します:Ray TracingとM...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

コンテナ内のdiv用のスムーズな左右のCSSアニメーションを作成する方法は?左右のムーブメントのための一般的なCSSアニメーション この記事では、一般的なCSSアニメーションを作成して、その容器の端に到達する左右に移動することを探ります。このアニメーションは、その未知の長さに関係なく、絶対的なポジショニングで任意のdivに適用できます。これは、100%で、divの...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

コンテナ内のdiv用のスムーズな左右のCSSアニメーションを作成する方法は?左右のムーブメントのための一般的なCSSアニメーション この記事では、一般的なCSSアニメーションを作成して、その容器の端に到達する左右に移動することを探ります。このアニメーションは、その未知の長さに関係なく、絶対的なポジショニングで任意のdivに適用できます。これは、100%で、divの...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

「JSON」パッケージを使用してGOでJSONアレイを解析する方法は?json arrays in jsonパッケージ 問題: 次のGOコードを検討してください: タイプjsontype struct { 配列[]文字列 } func main(){ datajson:= `[" 1 "、" 2 "...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

「JSON」パッケージを使用してGOでJSONアレイを解析する方法は?json arrays in jsonパッケージ 問題: 次のGOコードを検討してください: タイプjsontype struct { 配列[]文字列 } func main(){ datajson:= `[" 1 "、" 2 "...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

Node-MYSQLを使用して単一のクエリで複数のSQLステートメントを実行するにはどうすればよいですか?node-mysql in node.jsでのマルチステートメントクエリサポート、ノード-Mysqlパッケージを使用してnode-mysqlを使用してnode-mysqlを使用して、1つのクエリを使用してnode-mysqlの記録を使用して、1つのクエリで複数のsqlステートメントを...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

Node-MYSQLを使用して単一のクエリで複数のSQLステートメントを実行するにはどうすればよいですか?node-mysql in node.jsでのマルチステートメントクエリサポート、ノード-Mysqlパッケージを使用してnode-mysqlを使用してnode-mysqlを使用して、1つのクエリを使用してnode-mysqlの記録を使用して、1つのクエリで複数のsqlステートメントを...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

PostgreSQLの各一意の識別子の最後の行を効率的に取得するにはどうすればよいですか?postgresql:各一意の識別子の最後の行 を抽出します。次のデータを検討してください: select distinct on (id) id, date, another_info from the_table order by id, date desc; データセット内の一...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

PostgreSQLの各一意の識別子の最後の行を効率的に取得するにはどうすればよいですか?postgresql:各一意の識別子の最後の行 を抽出します。次のデータを検討してください: select distinct on (id) id, date, another_info from the_table order by id, date desc; データセット内の一...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

最大カウントを見つけるときにmysqlで\ "無効なグループ関数の使用を解決する方法\"エラーは?mysql を使用して最大カウントを取得する方法mysqlでは、次のコマンドを使用して特定の列によってグループ化された値の最大値を見つけようとする際に問題に遭遇する可能性があります。 emp1グループからmax(count(*))を名前で選択します。 エラー1111(HY000):グル...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

最大カウントを見つけるときにmysqlで\ "無効なグループ関数の使用を解決する方法\"エラーは?mysql を使用して最大カウントを取得する方法mysqlでは、次のコマンドを使用して特定の列によってグループ化された値の最大値を見つけようとする際に問題に遭遇する可能性があります。 emp1グループからmax(count(*))を名前で選択します。 エラー1111(HY000):グル...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

ChatBotコマンドの実行のためにリアルタイムでstdoutをキャプチャしてストリーミングする方法は?コマンド実行からリアルタイムでstdoutをキャプチャする 再起動のライン(コマンド): print(line) このコードでは、subprocess.popen()関数を使用して指定されたコマンドを実行します。 stdoutパラメーターは、subprocess....プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

ChatBotコマンドの実行のためにリアルタイムでstdoutをキャプチャしてストリーミングする方法は?コマンド実行からリアルタイムでstdoutをキャプチャする 再起動のライン(コマンド): print(line) このコードでは、subprocess.popen()関数を使用して指定されたコマンドを実行します。 stdoutパラメーターは、subprocess....プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

動的にサイズの親要素内の要素のスクロール範囲を制限する方法は?垂直スクロール要素のcss高さ制限の実装 インタラクティブインターフェイスで、要素のスクロール挙動を制御することは、ユーザーエクスペリエンスとアクセシビリティを確保するために不可欠です。そのようなシナリオの1つは、動的にサイズの親要素内の要素のスクロール範囲を制限することです。ただし、マッ...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

動的にサイズの親要素内の要素のスクロール範囲を制限する方法は?垂直スクロール要素のcss高さ制限の実装 インタラクティブインターフェイスで、要素のスクロール挙動を制御することは、ユーザーエクスペリエンスとアクセシビリティを確保するために不可欠です。そのようなシナリオの1つは、動的にサイズの親要素内の要素のスクロール範囲を制限することです。ただし、マッ...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

PHPを使用してXMLファイルから属性値を効率的に取得するにはどうすればよいですか?XMLファイルから属性値をPHP の取得します。提供されている例のような属性を含むXMLファイルを使用する場合: $xml = simplexml_load_file($file); foreach ($xml->Var[0]->attributes() as $att...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

PHPを使用してXMLファイルから属性値を効率的に取得するにはどうすればよいですか?XMLファイルから属性値をPHP の取得します。提供されている例のような属性を含むXMLファイルを使用する場合: $xml = simplexml_load_file($file); foreach ($xml->Var[0]->attributes() as $att...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

数字のみの出力で単一の数字認識のためにPytesseractを構成するにはどうすればよいですか?pytesseract ocrを備えたpytesseract ocr pytesseractのコンテキストで、単一桁を認識し、数字を抑制するためにテッセラクトを構成します。この問題に対処するために、Tesseractの構成オプションの詳細を掘り下げます。単一文字認識の場合、適切な...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

数字のみの出力で単一の数字認識のためにPytesseractを構成するにはどうすればよいですか?pytesseract ocrを備えたpytesseract ocr pytesseractのコンテキストで、単一桁を認識し、数字を抑制するためにテッセラクトを構成します。この問題に対処するために、Tesseractの構成オプションの詳細を掘り下げます。単一文字認識の場合、適切な...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

Firefoxバックボタンを使用すると、JavaScriptの実行が停止するのはなぜですか?navigational Historyの問題:JavaScriptは、Firefoxバックボタンを使用した後に実行を停止します ユーザーは、JavaScriptスクリプトが以前の訪問ページを介して回復したときに実行されない問題に遭遇する可能性があります。この問題は、ChromeやInt...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

Firefoxバックボタンを使用すると、JavaScriptの実行が停止するのはなぜですか?navigational Historyの問題:JavaScriptは、Firefoxバックボタンを使用した後に実行を停止します ユーザーは、JavaScriptスクリプトが以前の訪問ページを介して回復したときに実行されない問題に遭遇する可能性があります。この問題は、ChromeやInt...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

匿名のJavaScriptイベントハンドラーをきれいに削除する方法は?匿名イベントリスナーを削除する]イベントリスナーを追加する要素を追加すると、柔軟性とシンプルさを提供しますが、要素自体を置き換えることなく挑戦をもたらすことができます。 element? element.addeventlistener(event、function(){/はここで動作し...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

匿名のJavaScriptイベントハンドラーをきれいに削除する方法は?匿名イベントリスナーを削除する]イベントリスナーを追加する要素を追加すると、柔軟性とシンプルさを提供しますが、要素自体を置き換えることなく挑戦をもたらすことができます。 element? element.addeventlistener(event、function(){/はここで動作し...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿 -

java.net.urlconnectionとmultipart/form-dataエンコードを使用して追加のパラメーターを使用してファイルをアップロードする方法は?http requests を使用してファイルをhttpサーバーにアップロードしながら、追加のパラメーター、java.net.urlconnection、およびmultipart/dataエンコーディングを送信します。プロセスの内訳は次のとおりです。エンコーディングには、要求本体を複数...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

java.net.urlconnectionとmultipart/form-dataエンコードを使用して追加のパラメーターを使用してファイルをアップロードする方法は?http requests を使用してファイルをhttpサーバーにアップロードしながら、追加のパラメーター、java.net.urlconnection、およびmultipart/dataエンコーディングを送信します。プロセスの内訳は次のとおりです。エンコーディングには、要求本体を複数...プログラミング 2025-04-08に投稿

中国語を勉強する

- 1 「歩く」は中国語で何と言いますか? 走路 中国語の発音、走路 中国語学習

- 2 「飛行機に乗る」は中国語で何と言いますか? 坐飞机 中国語の発音、坐飞机 中国語学習

- 3 「電車に乗る」は中国語で何と言いますか? 坐火车 中国語の発音、坐火车 中国語学習

- 4 「バスに乗る」は中国語で何と言いますか? 坐车 中国語の発音、坐车 中国語学習

- 5 中国語でドライブは何と言うでしょう? 开车 中国語の発音、开车 中国語学習

- 6 水泳は中国語で何と言うでしょう? 游泳 中国語の発音、游泳 中国語学習

- 7 中国語で自転車に乗るってなんて言うの? 骑自行车 中国語の発音、骑自行车 中国語学習

- 8 中国語で挨拶はなんて言うの? 你好中国語の発音、你好中国語学習

- 9 中国語でありがとうってなんて言うの? 谢谢中国語の発音、谢谢中国語学習

- 10 How to say goodbye in Chinese? 再见Chinese pronunciation, 再见Chinese learning